What is Next?

Family, friends, employees and clients ask me what is next and how to manage so many unknowns? This is what I tell them, and what I am planning for the rest of 2020 and going into 2021. I start any discussion with three key points:

1. You can’t force a schedule or timeline on something like a pandemic or disaster.

The thing about pandemics and disasters, in general, is that they take their own time and run their own schedule. A schedule that never really ends. There have been entire years that, to me, are defined by world crises. That is how I remember them. Imagine what that must mean to my family? Take the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami. Day after day going from meetings, to open air temples holding thousands of deceased, punctuated with the anguished cries of families finding the loved ones they didn’t want to find among the dead. Second only to the cries of those who never found their loved ones. So, we don’t get to go back to the way things were. We don’t get time back, and it is pointless to try and impart a schedule on these events. It is okay to mourn the past, to be angry of what we have lost in things, gains in employment, and feeling like we have been knocked down, but then to reflect and focus on solving the current problems and looking forward to the new normal. Because there is always some good and there is always recovery.

2. It can be worse, and the world has lived through worse.

I have seen worse in multiple senses of the current pandemic. I have seen larger number of dead at one time and one place then any one place is seeing today- for example, the Haitian Earthquake. I saw people struggle after 9/11, wondering, will we ever be able to fly again? Or feel safe? I am part of a generation that questioned if we were at the end of the world during the Cold War. For me it was very personal. I was a 22-year old Commissioned Officer at the control of three nuclear missiles during that time period. Each and every time the klaxon sounded, I wondered was it for real or for a drill. We didn’t always know, and those that study history know at times we were close – too damn close to launching.

3. There are more knowns than unknowns.

There are more things you can control than you cannot. I don’t waste energy, time or resources on the things I cannot control. Instead I concentrate on being prepared and managing the expected consequences and understanding the most likely course the event will take. I don’t know the time schedule an event will follow, but for the most part I do the know the route it will take. That is powerful for a sense a personal control. In a crisis, even such as COVID-19 there is a lot more known than unknown. Past experiences, study of previous events, and focusing on the consequences are great ways to have that personal control.

So, what does all that mean to COVID-19? Point one – the million-dollar question: when do all the restrictions end and everything will be normal again? Pandemics are not single wave events; being over is not the absence of new cases – unless that is worldwide and sustained. Pandemics come in waves, not years apart but months apart. What triggers the subsequent waves? Historically it is the relaxation of restrictions, failure to adopt lessons learned, or underestimating the seriousness of the virus.

For example, in March 1918, the first outbreaks of a flu-like illness showed up in the US, and similar sporadic activity through Europe and possibly Asia occurred over the next 6 months. In April of 1918 (somewhat ironically), the first mention of influenza appears in a public health report. This is considered the first wave. At the time, there was notice but not much concern.

Then in September 1918, the second wave begins. It lasts until November 1918. It is by far the deadliest wave. This was the wave responsible for most of the deaths. In the US for example, the most current totals (they have been revised several times) estimate 185,000 Americans alone died in October 1918. If you had been alive at this time you would have seen cold storage plants being used as morgues, urgent calls for nurses (many were still overseas with the Army fighting WW1), authorities closing theaters, movies, schools and prohibiting public gatherings. Finally, rules requiring the wearing of masks in public. Sound familiar?

Policemen in Seattle wearing masks made by the Red Cross, during the influenza epidemic. December 1918. Credit: National Archive

Streetcar conductor in Seattle not allowing passengers aboard without a mask. 1918. Credit: National Archive

Typist wearing mask, New York City, October 16, 1918. Credit: National Archive

Then in January 1919, or 10 months after the first illness; 2 months after the last, and the 3rd time of people thinking it was over, the third wave strikes, not as deadly as the second, but deadlier than the first.

So, you might ask: are we in our first wave or second wave already? The answer probably depends on where you are in the world when reading this. Will this pattern repeat itself? I don’t know. You could go into the all factors that influence this, both good and bad in the last hundred and one years. When I do that, I pretty much end at neutral, perhaps a little more to the positive but not enough to change my behaviors.

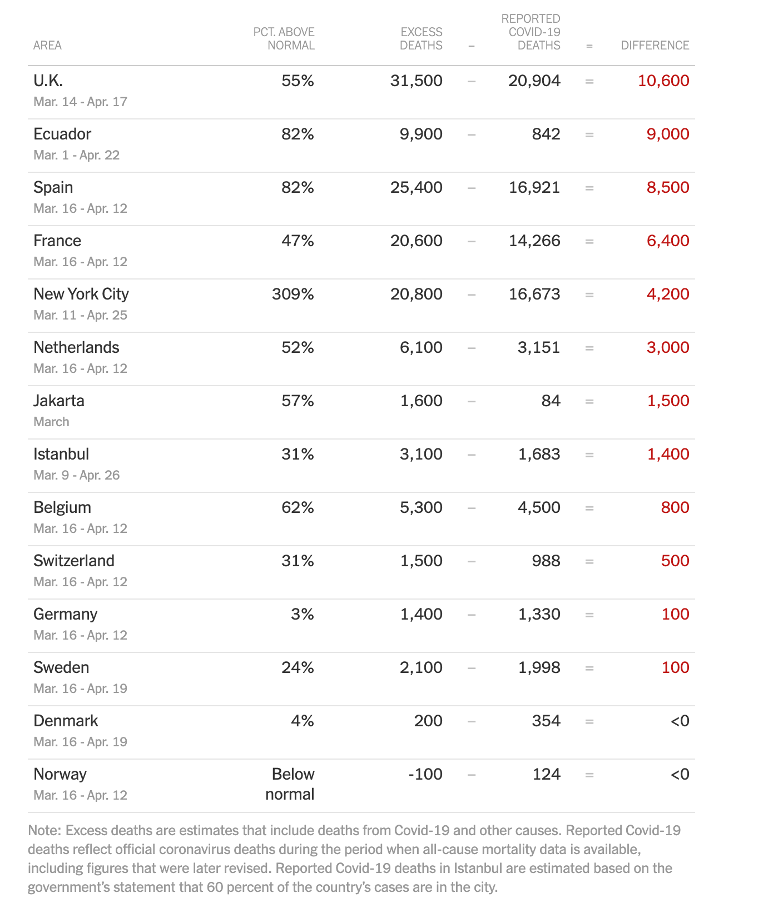

Now, let’s add to what we do know. We know that significantly more people around the world died during April 2020 then died during the same period in multiple previous years, even with population gain taken into account.

Sadly, what we focus on is: in people who have the virus, what percentage die? Certainly, that information is important for research, but how useful is it right now? Does anyone really want to make the argument that if the percentage of people who die is low enough then it is okay, given the high numbers of dead we already have? The information that is important right now is clear, and that is a large number of people are dying and in some places are continuing to die at a rate considerably greater than any other recent event. It doesn’t really matter right now if the fatality rate is .003% or 5%. COVID-19 is killing lots of people in a sustained manner over time. That is the bottom line.

I know this, not just because of the example below, but because we have teams operating in the field. This is the big picture summary from the New York Times[i]

We know that COVID-19 is easy to transmit from person to person. People are focused on what percentage of the population have COVID-19. That is something we would all like to know but collecting that information will take time. Time to develop, verify and produce sufficient testing resources. However, we do have useful information now that is much more important at the response and reopening decision-making levels. That is the Ro or “R” naught number. The is the number which reflects how contagious a disease is.

As early as February, the World Health Organization stated that COVID-19 was easily transmittable and would likely have a high Ro. Today the CDC believes that current value is 5.7.[ii] For reference, the median Ro value for the seasonal flu is 1.46[iii]. A practical example of what this means for people looking at community spread, is the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) on the Chicago Illinois case. One person, over the course of five days, attended a meal, a funeral and birthday party after traveling out of state and was experiencing mild respiratory symptoms. This person is the index patient for a further 15 cases, three of which were fatal.[iv]

We know that herd immunity is not arbitrary nor just letting people get sick. For many viruses (not all) simply having a single exposure to the virus does not equate to immunity or herd immunity in large numbers. Going back to the seasonal flu for example, people have developed some immunity from repeated exposure and increased immunity is gained by annual vaccines. However, when a virus has a Ro of 5.7, 82% of the population has to be immune through vaccination or prior infection to achieve herd immunity to stop transmission.[v] Does anyone think we are there?

We also know that beyond the loss of life – which I think was best referred to by the science journalist Laura Spinney “as millions of private tragedies”[vi] – the economic toll, the mental health toll and levels of anxiety are likely to be enormous and will in themselves cause loss of life. I remember sitting with boards after 9/11 and the thousand-yard stares discussing when it would be okay to fill the positions of those that had died, or when it would be okay to advertise for tourism in Bali. Successful economic recoveries and adjustments are also not an unknown nor are the likely changes. They are fairly predictable. That is a subject of the next paper. Achieving those means, accepting the pandemic has occurred. We failed to stop it and we must go forward, not backwards.

People want an individual sense of control; they are ready for this to be over because it is taking too much time. Time is probably the single most common measurement in the world. Something we all understand and sadly, for so many people right now, it is measured in terms of loss. However, because of the many things we know – and one of those is that we don’t control the timeline – I am supporting the phased approach many governments are taking and avoiding situations, people or areas that are not taking this approach, so the time spent is not in vain.

Besides my work in dealing with the more typical mass fatalities, I spent a portion of my army career and have worked on multiple projects dealing with the effects of nuclear (radiological) biological, and chemical agents, a pandemic of course falls under the biological Category. Beyond numerous books, I often refer to these as common resources –

- Oxford Academic, The Journal of Infectious Diseases

- The Human Mortality Database

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports

- US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health

[i] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/21/world/coronavirus-missing-deaths.html?campaign_id=168&emc=edit_NN_p_20200429&instance_id=18058&nl=morning-briefing®i_id=106762960§ion=topNews&segment_id=26195&te=1&user_id=c2cc4f23984a933b85692c86ba0aef17

[ii] https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/7/20-0282_article

[iii] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25186370

[iv] https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e1.htm?s_cid=mm6915e1_w

[v] https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/7/20-0282_article

[vi] Pale Rider, the Spanish Flu of 1928 and How It Changed The World (I would recommend this book for anyone trying to understand and plan for what’s next.)